Being pastorally responsible for a group of 30 children as their form tutor is perhaps the greatest privilege and source of joy that teaching can bring. At one stage in my career, I became the form tutor of a class of 11-year olds as they began secondary school. I vividly recall meeting them on their first day: a mix of nervous energy and excitement for a fresh start. On that day, I taught them about integrity, gratitude and responsibility: three values I really wanted them to live and breathe daily. I also warned them about the harms of smartphones.

“Some of you might have smartphones already. I would urge you all to consider switching to a brick phone. Those of you who don’t have a smartphone – keep it that way! Smartphones steal your time away and are incredibly addictive.” Some of them listened. Others did not.

Over the next two years, I came to know these children very well. I would see them every morning as they came through the school gates, ensuring they had the right uniform. I’d lead them in for form time where I’d check they had brought their equipment, instilling in them a sense of personal responsibility. I’d teach them science for an hour each day. I’d spend break and lunch times with them, reminding them to serve food to each other and clear up after themselves. During afternoon form times, I’d celebrate what I’d seen them achieve that day and pick out what they needed to do to push themselves further the next day.

In short, I saw this class a lot and knew them very well.

One day, when they were in Year 8, I caught wind that a pupil had brought their phone into lessons. This surprised me because pupils are not allowed phones in school – they hand them in at the start of each day to ensure their day was smartphone-free. With the right permissions sought, I investigated a group chat to verify, where they had allegedly posted.

Scrolling through, I found the pictures he had taken. What a cheeky chap: several selfies of him pulling funny faces in lessons emerged. As I was about to hand the phone back, something caught my eye in the image gallery of the group chat.

That’s when the pit of my stomach dropped.

It’s hard to describe the protective feeling you develop when you care pastorally for a group of children. You come in everyday to not only teach them your subject, but also help them to become better people. You invest in their character development. Are they getting better at taking responsibility for their actions? Are they working hard enough? Are they developing a less entitled and more grateful outlook in life? Are they building their resilience and seeking out opportunities to make the most that life has to offer? These are the things I would think about daily as their form tutor.

So when I stared at the screen and saw graphic images of dead bodies cut open, and sickening, sexually explicit images shared casually and commented upon frivolously – as if these were totally normal everyday posts – I felt a deep dread, fear and sense of grief for the lost innocence of the children in this group chat. How can my kids be involved in this?

I had known the dangers of smartphones for a long time, but the visceral experience of seeing that my own pupils were casually exposed to and were sharing these unbearably vile and disturbingly graphic media, evoked a stronger emotional response than I had felt about smartphones before.

When I individually invited each of the parents of the pupils involved to meet with me, I asked them if they wanted to see what sorts of things their children had been exposed to. I vividly recall one parent agreeing, and despite having been warned, wailing loudly in horror, averting her eyes in disgust. That cry of horror will always stay with me. The thought that her little boy has witnessed something so debasing was understandably difficult to grapple with.

David’s struggles with time

The following is based on several conversations I had with various pupils aggregated as one, a fictional ‘David’. The screen time images are all AI generated but are representative of real screen times I have encountered.

On a Monday in May, a Year 9 boy called David was in detention again. This time it was for not doing well enough in a quiz, which tested him on the key things he practised for his homework at the weekend.

“Sir, I just don’t have time to revise properly. I get so much homework.” I’d heard it a million times before but I never make assumptions – I thought I’d verify. And no, I don’t mean I investigated how much homework he was getting. I asked David if he had a smartphone. “Yes, sir” he said, looking perplexed; after all, what’s a smartphone got to do with his quiz? “Let’s have a look at your screen time together. Maybe you are spending more time on it than you realise.” Hesitant at first, he agreed once he was sure this wasn’t a ruse confiscate his phone. Here is what I found:

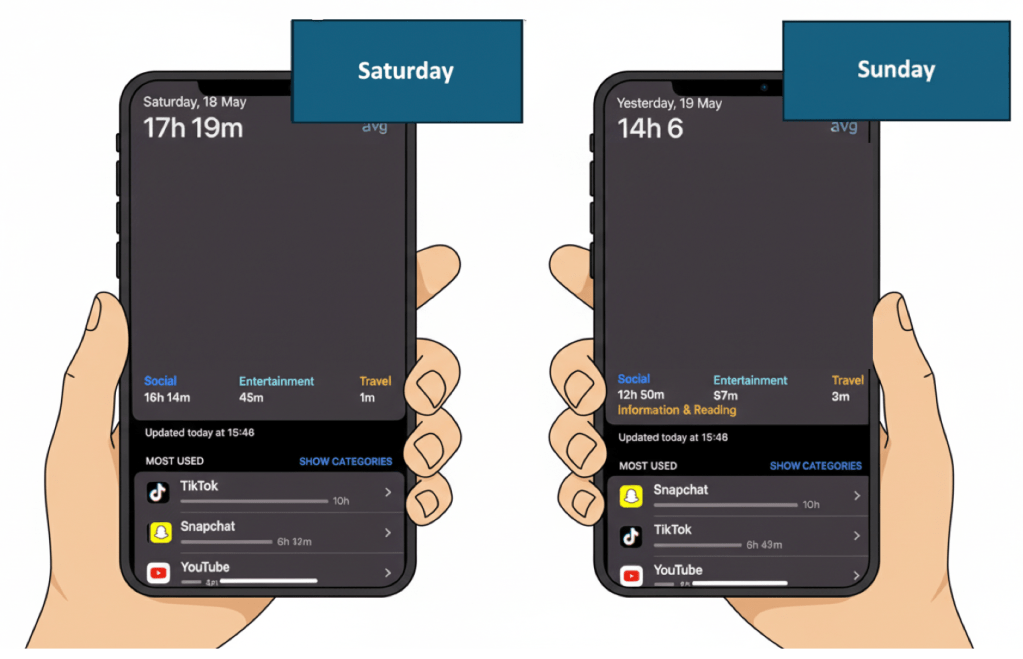

David had spent seventeen hours on Saturday and fourteen hours on Sunday on his smartphone. Nearly all of this time was spent on two apps: TikTok and Snapchat.

Let that sink in.

Pupils I know who spend this much time on their phones often only get two or three consecutive hours of sleep. Their hour-by-hour screen time looks like the example below:

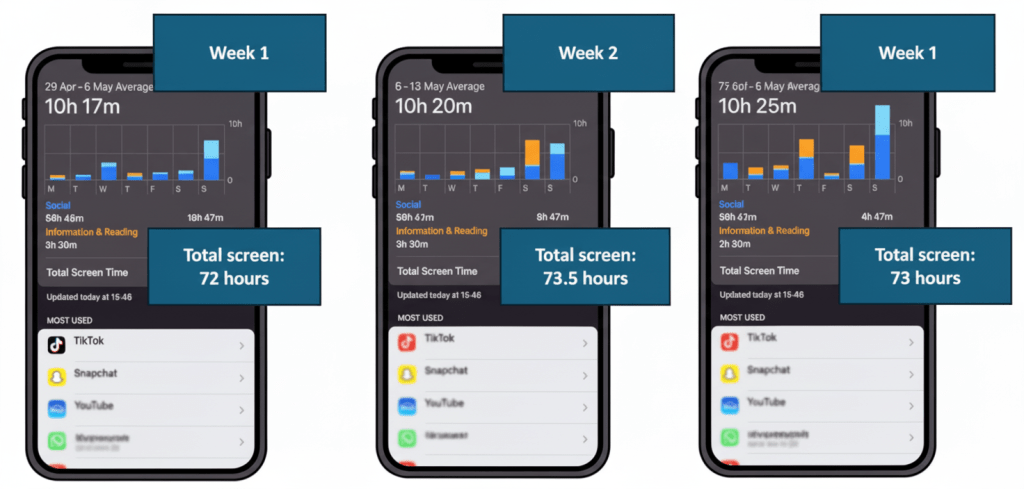

I wanted to know if this was typical so we looked at David’s previous weeks’ average screen times and found the it to be over 70 hours per week. That’s nearly two full times jobs: one with Snapchat and one with TikTok.

Is this unusual? Although this example is more extreme, here is a sample of screen times of three pupils in three different year groups on a Monday where there was no school.

I typically find that on school nights, pupils spend around 4-6 hours on their phones. On days off school, it can be at least 8 hours.

Putting it all together

The stories I’ve told in this post highlight a few things. First: once childhood and innocence are lost, they are hard to get back. Children who have seen awful things on the internet cannot un-see them. The only way to guarantee that children do not get exposed to the worst on the internet is to never allow unsupervised internet access. This is much easier if we do not hand them a smartphone.

Second, a smartphone changes children. It makes them less hard working. It makes them less kind. We all know that it is far easier to say something nasty when we cannot see the victim in front of us. Children have the added weight of peer influence. Typing ‘LOL’ in response to a cruel joke on a group chat gives you kudos; it lets you fit in. But a ‘LOL’ one day becomes typing a nasty comment the next. Group chats can so easily chip away at the values of a child that we want to build in them: integrity, kindness and responsibility. Every ‘like’ of a nasty comment, ‘share’ of an abusive video, comment on a mocking meme, every spreading of a rumour – all of these morally wrong actions contribute to the erosion of a child’s character. This invariably and inevitably spills over into their actions in real life.

Third, children have no chance against the magnanimous gravitational pull of social media. Millions of pounds are invested by social media companies to make virtual spaces too alluring for a teenager’s mind to resist autonomously. They are designed to create an artificial sense of belonging, prestige and popularity. This is damaging their mental health, as Jonathan Haidt explains in ‘The Anxious Generation’. Smartphones cannot replace the real sense of belonging you get when you spend time with your grandma, cracking jokes until your bellies hurt; or the prestige and popularity you win by grafting at the piano for hours on end and developing a skill that will stay with you for life.

I haven’t even touched upon the dangers of grooming; the unethical algorithms of social media feeds; the luring of children to sell drugs and make fast money. These are the more shocking and more extreme, though sadly not too infrequent, potential repercussions of giving children smartphones.

So what’s the answer?

Choose brick phones instead of smartphones for your child until the age of 16. I do not believe a child is safer with unsupervised internet access. They are not more safe on the roads with a very expensive device in their hands on their way to and from school.

To those who say it is an impossible tide to turn, I’d ask you to consider differently. Over the years, many of my tutees never ended up getting a smartphone, or ditched their smartphone for a brick phone. More and more parents are choosing brick phones. Schools can play a big role in informing parents. After all, schools have 1000s of case studies and direct experience of the issues smartphones cause at scale, which can be invaluable for parents to make an informed decision.

The effects of the choice about whether or not to give a child a smartphone are always so visible; you see it in lessons and you see it in playground behaviour. Children with smartphones are more likely to gravitate towards each other and gossip at break time. Children with brick phones tend to play games with each other in the playground.

This is why I am in favour of banning mobile phones in schools across the country, and for this to be the law. As the screen times above show, the only thing stopping these children from spending even more time on their smartphones is the fact that their school has banned smartphones. Thank goodness; it’s a significant break in the day from both the loss of their innocence and the fuel to their mental-health-destroying addiction.

Who’s with me?