‘Turn & talk’ is one of the techniques I use most in my classroom – perhaps 20 or more times in any given 50-minute lesson. I recently shared a clip of what this might look like on Twitter (click here).

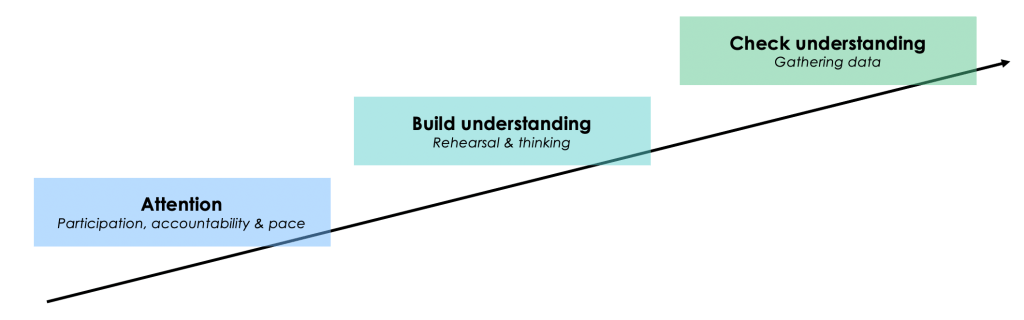

My strategy for explicit instruction involves asking questions in three phases. Phase 1 questions include firing out high-frequency ‘checks for listening’. These are simple questions all pupils are expected to answer (either through choral response or ‘all hands up cold calling‘) and serve to interrupt the loss of attention. Phase 2 questions involve lots of rehearsal and give pupils a chance to grapple with or generate new ideas. The goal is to build understanding to the point where it is secure. Phase 3 questions are ‘checks for understanding‘ and their responses give the teachers feedback about whether to move on to the next part of the explanation or not. (In the linked clip, I use the data I gather from a Phase 3 question to decide that more rehearsal is needed, and so use a Phase 2 question in the form of a ‘turn and talk’.)

I didn’t used to use Phase 1 (attention) and Phase 2 (rehearsal) type questions – I did not check pupils are listening and I did not give pupils sufficient opportunity to rehearse new ideas. This meant that the type of questions I did typically ask (Phase 3: checks for understanding) yielded a much lower proportion of correct answers than if I had used all three phases of questioning.

Cycling through the three phases of questioning has transformed my teaching: I am now setting students up to succeed far better than before, which is evident when they then answer ‘checks for understanding’ more successfully.

‘Turn and talk’ is a crucial strategy in my toolbox for this. It allows 50% of the class to answer a question at the same time and is perfect for Phase 2 questioning. This includes rehearsal, generating ideas & making feedback land. Let’s explore each of these in turn.

Rehearsal: building fluency

As you teach new ideas explicitly, give pupils the chance to practice the vocabulary or practice explaining the ideas themselves. For example, if you are teaching pollination & plant fertilisation, you might explain that pollination is when pollen lands on the sticky stigma. Immediately, you might ask pupils to rehearse this first step with their partners: “Tell your partners a sentence with the words: pollination and stigma – go!” 20 seconds later, ask for hands up and pick someone to share. Then you explain that after pollination the pollen grows a pollen tube that goes down the style and into ovary of the flower. You have now used six ‘tier three’ words (pollination, pollen, stigma, style, pollen tube and ovary) and you are only just getting started! The pupils will definitely welcome more chances to rehearse. “Tell your partners what has happens after pollination – use the image and labels on the board to help you – go!” In essence: give two facts of a process, rehearse both, give the third fact, rehearse it, give a fourth fact, rehearse all four etc. All of this forms part of ‘Phase 2’ questioning in the ‘Three Phrases of Questioning’ model of explicit instruction.

Can you imagine what would happen if you explain the whole process of pollination & fertilisation without rehearsal and then get students to answer some ‘check for understanding’ questions? Most would struggle to get the answers right. But with rehearsal (phase 2) the proportion would shoot up. If you also pepper your explanation with phase 1 questioning (e.g. checks for listening), then the chances of success increase even more.

Generating ideas: a ‘turn and talk’ gives all pupils the time and opportunity to test out their suggestions with their partners. “Who can suggest what the link between the sweet nectar of flowers and pollination might be? [Wait time – survey hands up]. Tell your partner what you are thinking – go!” These types of questions essentially allow pupils to connect two bits of knowledge on their own.

Making feedback land: if we have just done some self-assessment after an independent practice task where I have given pupils feedback, a ‘turn and talk’ can be used for pupils to share with their partners where they went wrong or what they learned from the feedback. So many teachers give feedback and then forget to check the class has actually listened or understood the feedback. This is one strategy to ensure feedback lands.

In short, ‘turn and talk’ is great for building understanding, whether that gives pupils the chance to grapple with ideas that have been explicitly taught by practicing rolling around the new vocabulary and articulating what they have come to learn so far, or whether it is a chance for pupils to make new connections or generate ideas based on what they have been taught. (This latter point explains why I am now updating what I called Phase 2 questioning in a previous blog from ‘rehearsal’ to ‘build understanding’).

The mechanics of a ‘turn and talk’

- Every student knows who their partner is – the person next to them that they will turn and talk to.

- I ask a question that requires a full sentence answer.

- If anywhere between 50-100% of hands go up, I make the decision to use turn and talk: “Door side partners first – go!” Sometimes, rather than asking a question I might just say, “Tell your partners what the first two steps of the cell cycle are. Window side first – go!”

- There is a buzz in the room. Every single pair turns to face each other. They each say the answer. I give between 5 and 15 or 20 seconds (yes, that is a really short time!) and then I say…

- “3, 2, 1, hands up!” Every single student in the room has their hand up in total silence by the time I reach the words ‘hands up’.

- I select a student and all hands go down, back in SLANT. This is effectively an “all hands up warm call” since the students have rehearsed their answer.

Pitfalls

Do not fall into the following ‘turn and talk’ traps:

- Using ‘turn and talk’ for one word answers. Use a choral response instead! It will sound crisper. Ask your one-word-answer question, wait for all hands up, and then say: “On 3: 1,2,3!” You’ll get a beautiful response in unison.

- Not directing the student who talks first. The risk is that one pupil in each pair might dominate the conversation every time and the other pupil may never get the chance to rehearse. There are times when I don’t specify who goes first – usually when I’m expecting a more generative response where some pupils will have an answers to share and others might not. But most of the time, specify who goes first. Mix it up each question: “Door side first – go!” or “Window side first this time – go!”

- Stopping the ‘turn and talk’ too early or too late. I usually say ‘321 hands up’ when I hear the buzz start to fade. Doug Lemov calls this ‘cresting the wave’. No point in waiting for everyone to finish – you never want pairs to fall silent. They should be continuously rehearsing to make the most of every second. No point interrupting a buzz if they are all busy talking and in the middle of rehearsing. Think ‘Goldilocks’.

- Not expecting all hands to go up. I expect every hand to go up because everyone has just practiced or heard some answers. Turn and talk is the perfect way to introduce a culture of ‘all hands up’ questioning. The more you expect all pupils to contribute the better they will all learn.

- Not insisting on full sentences. This would be a huge missed opportunity. Getting pupils to use full sentences is so powerful at ensuring pupils are connecting what they heard in your question to the answer they are giving. I remember once asking a pupil to give examples of organs and the pupil said “Heart”. I responded with, “In a full sentence please”. And they responded, “An example of an organ system is the heart!” Uh-oh! I wouldn’t have picked up that error if I hadn’t insisted on full sentences and the pupil’s understanding would have suffered. Don’t let your pupils suffer.

If you’d like to see more clips of this in action & and want to learn more about our approach to pedagogy, homework, quizzes & curriculum design, get tickets to our Science Conference which is taking place on Monday 22nd January at Ark Soane Academy in Acton, London. Details here: https://www.eventbrite.com/e/ark-soane-science-conference-2024-tickets-772182226827?aff=ebdssbdestsearch

*******

If you are interested in working at Ark Soane Academy, we are hiring! Soane is a new secondary school that currently has Years 7-9. Join as we grow and help shape the school. Vacancies can be found here:

There is even a ‘quick apply‘ form where you can send in a speedy application. Any questions – feel free to send me a DM on Twitter: @Mr_Raichura

*****

A really great blog – thanks for sharing, Pritesh! We talk about some of these strategies at my school, but haven’t yet drilled into the phases/order of these, and certainly not with precision that you explain. I’ve learned a lot from your Twitter feed and am very grateful that you share so much on your feed/blog. Your recent video was excellent, and very brave to share. I think you can be reassured that any criticism were from people who have never worked in schools, or from teachers who have never worked in areas that have the potential to be challenging through lack of school-wide structure/culture/clarity.

I have a Q, and I ask these in an absolutely non-critical way…

I understand the Michaela/Ark style of traditional teacher-centred pedagogy with knowledge transmission at its heart. I’m interested to understand whether there’re opportunities for practical elements within lessons (what the literature would describe as “student-centred”), where pupils are able to apply their knowledge to different problems?

2nd question relates to pupils who struggle with attention. The strategies in your video are absolutely incredible for pupils with ADHD or other attention issues. The fact that critics (particularly those who work in schools) can’t recognise this is frustrating! I just wanted to know how these pupils might be catered? Is there ever an opportunity for “downtime”? Obviously I don’t think that we should lower expectations for any pupils (often a huge pitfall in many schools!) but I am increasingly learning how exhausting learning can be for specific pupils with specific needs such as ADHD, especially when going from lesson to lesson and particularly if they’re learning as much as they clearly do at Ark Soane! I wondered whether they had an opportunity to have a brief in-class ‘brain-break’ or ‘reset’ to help them regulate (if needed), perhaps during independent work?

You only see so much from a 1 minute clip, and I’m interested to understand more about what happens next, or in future lessons, and perhaps across different subjects.

I’m asking this as a primary teacher – not a science teacher – so the pedagogy I see everyday is understandably different to the secondary sector.

Thanks so much – hope you see this!

LikeLike

Thanks for your kind words Odile. There are lots of opportunities for pupils to apply their knowledge. I wouldn’t call this “student-centred” however. The purpose of explicit instruction is to ensure pupils have the knowledge they need to be able to truly understand the subject at hand. So lots of questions would naturally involve thinking hard.

To answer your second question about focus: lessons involve lots of opportunities for independent practice too, so this allows all pupils to direct their focus entirely to their own work. But I’ve never had issues with pupils simply unable to focus for an entire lesson. This is probably because overall the culture is that of 100% so lessons are really calm & without distraction. There are lots of opportunities to rehearse and participate as well as focus independently.

LikeLike

Great article, thank you! We’re embedding turn and talk in our school currently and this provides a great framework to embed it successfully. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Do your pupils work hard enough? | Bunsen Blue

Pingback: Choral Response and ‘I Say You Say’ | Bunsen Blue

Pingback: Means of Participation: Low Effort – High Impact – Selective Blogging